Humanizing OER

Bridging Mental Health and Accessibility in Education

Welcome back to the OERganic newsletter! Since our last edition, I've been reflecting deeply on the journey of humanizing educational resources and processes. As many of you know, my mission goes beyond making education affordable and accessible—it's about creating a supportive, inclusive, and empathetic environment for all.

Lately, I've been navigating the complexities of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) process at my workplace to get the right accommodations for my mental health. This experience has highlighted the need for more human-centered approaches in every aspect of our professional lives. The process has felt less supportive and more like a series of hurdles designed to box me into a rigid framework. It has been a poignant reminder of why our work in OER is so crucial.

Struggling with Mental Health

Living with Bipolar Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, and Attention Deficit Disorder presents daily challenges that affect both my professional and personal life. Currently, I'm working with behavioral health doctors through my employer's health insurance. While the initial visits cost $10, I recently faced a paywall of $140 to keep an appointment with my medication management doctor, with no way to contact my provider directly. As I write this, my therapy appointment paywall is $278 for my session tomorrow. I am still figuring out my medication, which is an experimental process.

To help maintain and manage my bipolar symptoms and fluctuations, I have adopted a small dog that I am training as my psychiatric service animal. Additionally, while I already have a flexible hybrid schedule, a more adaptive work/life balance would better meet my needs. These support systems are crucial for my well-being and enable me to perform my essential job functions as the OER librarian, which require a high level of organization, creativity, and adaptability—traits that are often in flux due to my mental health conditions.

For years, I have worked in various educational settings—public education, professional education, and now higher education—without the correct diagnosis, medication, or support. I am ready to be seen as a whole person, to receive the necessary support, and to thrive both at work and in life.

Navigating the ADA Process

The ADA process has been an eye-opener. Despite its intention to support, the process often seems geared towards physical disabilities, with little consideration for mental health. My experience has been one of micromanagement, wrapped in a veneer of help, but often ending in "no, we can't help with that." ADA laws are complex and sometimes lack specific guidelines for mental and unseen disabilities. Navigating these laws can be challenging, and it appears that the interpretation and application of these laws by employers may result in a series of rigorous steps for employees seeking accommodations.

I had hoped that providing detailed research and extensive explanations about my condition and the accommodations I need would be enough. Instead, I was asked to fit all this nuance into rigid forms, making the process feel more like a bureaucratic exercise than a genuine attempt to understand and accommodate my needs. Being seen and heard as a human being should not be this challenging.

Humanizing OER

My experiences with mental health deeply influence my approach to OER. I believe in making OER accessible and inclusive for all students, including those with mental health challenges. This involves using inclusive language, offering flexible deadlines, and providing diverse content that reflects a variety of perspectives and experiences.

In my role, I work closely with faculty to break down barriers in education and knowledge, ensuring that courses are human-centered and communicate a culture of care. It is heartbreaking that while I strive to humanize education for others, I often feel like just another number in my own workplace. Humanizing processes means more than face-to-face interactions—it means understanding, empathy, and flexibility.

Final Thoughts

Education should be a human-centered endeavor in all its aspects. As we continue our work in OER, let's strive to create environments that support mental health and inclusivity. I invite you all to share your feedback and personal stories, as your experiences are invaluable in shaping a more empathetic and supportive educational landscape.

Thank you for being part of this journey. Together, we can make education more accessible, inclusive, and human for everyone.

In this article, "we" and "us" refer collectively to myself, individuals engaged in work related to Open Educational Resources (OER) or Open Pedagogy, and subscribers who have chosen to engage with this content. Our shared commitment to advancing open education practices unites us in this discourse.

It is important to note that the thoughts and opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author and contributors. They do not reflect the views, positions, or policies of our respective employers. The perspectives provided are based on personal experiences and professional insights into the field of open education.

Edited Friday, June 28th, 2024.

OERganic: Cultivating Humanity in Education

"Imagine if [education could] be more effective, efficient, ethical, and beautiful. What would it look like?"

- The Imagine If... thinking routine was developed by Project Zero, a research center at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Redefining Access: OER's Financial and Beyond

As an Open Educational Resources (OER) librarian at the University of Texas at Arlington (UTA), I've engaged in numerous enlightening discussions within our community. I've observed a fascinating trend: the initial appeal of OER often lies in its financial benefits. The ability to reduce or eliminate costs is a powerful draw, and rightly so—the economic impact of OER is significant and tangible.

Definition of Open Educational Resources

However, as my understanding of the open movement and its pedagogy deepens, I'm discovering an array of benefits that extend far beyond mere cost savings. My dialogues with faculty members reveal a shared enthusiasm for adopting, remixing, and creating OER not only as a cost-effective measure but as a way to tailor and contextualize their courses. This custom approach lends itself to a more personal, relevant educational experience.

Personalizing Learning: The OER Approach at UTA

There's a palpable desire among educators to expand their students' horizons. They seek to afford their pupils global exposure for their research and scholarship, even at the undergraduate level. It's heartening to witness faculty facilitating opportunities for students to graduate from UTA as published OER authors—authors whose works will resonate and be utilized by a global audience of students, educators, and community members.

Many faculty members are actively identifying and bridging gaps in available resources within their fields. They strive to infuse their disciplines with diverse perspectives, to amplify marginalized voices, and to ensure that human consideration triumphs over stagnant theory.

Human-Centric Education: The Core of Open Philosophy

When faculty members choose to engage with OER, they send a powerful message to their students: You are seen, you are valued, and you matter. It's this human-centric ethos that makes students feel truly acknowledged and cared for within their educational journey.

In my dialogue with students, the value of Open Educational Resources in shaping their learning is unmistakable. They’ve expressed how OER not only makes education more accessible but deeply resonates with their personal and academic narratives. This shift from passive absorption to active engagement in their educational materials is revolutionary. It reaffirms our mission at UTA: to create an inclusive and innovative academic environment where every student is acknowledged, valued, and empowered to contribute to the ever-evolving landscape of knowledge.

This is the conversation I wish to further, exploring the human impact of OER, learning from others, and spreading the word about these profound benefits. It’s not just about the resources; it’s about the people they empower and the lives they touch.

Starting Small: A Guide to Embracing Open

I want to share a book recommendation, Open: The Philosophy and Practices that are Revolutionizing Education and Science (2017) by Rajiv S. Jhangiani and Robert Biswas-Diener. The entire book is Open Access (free to read) and absolutely worth reading in its entirety. I don’t want anyone to not join this conversation because they don’t want to read a book. It is okay to start small. These are the chapters I suggest to faculty when they are brand new OER:

Introduction to Open (pp. 3-8)

Openness and the Transformation of Education and Schooling (pp. 43-66)

After engaging with these three chapters, I suggest exploring the other chapter titles and following what interests you.

From an educator’s perspective, I love that I am able to piece apart this book and share it with others in a way I feel would make sense. It allows me to tailor the support and collaboration I can provide. Educators can harness the flexibility of certain Creative Commons licenses to dissect and link directly to specific sections of openly licensed materials, tailoring the resources to their teaching needs.

I invite your reflection and dialogue:

How do the materials and course design we select shape the message we send to our students?

In what ways could OER, Open Pedagogy, and Open Culture enhance the educational journey for your students?

Share your thoughts, your disciplinary connections, and the challenges you believe OER could address.

As an OER Librarian, I’m here to dive deep into the world of open education and bring back what you need most. What are you curious about? What challenges can I help you tackle through research and insights? Let me know what topics you’d like to see covered in this newsletter. Your feedback will shape our content, ensuring it’s always relevant and useful. Let’s learn and grow together in this exciting field of open education.

Final Notes: Ethical AI Use in Our Newsletter

In the creation of this newsletter, I am committed to the ethical use of artificial intelligence (AI) as a tool to enhance our exploration of Open Educational Resources (OER). I use AI responsibly to refine content, generate ideas, and ensure clarity and engagement in our discussions. However, I always ensure that the final content aligns with our core values of transparency, accuracy, and inclusivity.

I believe in harnessing the capabilities of AI to complement our human creativity and intelligence, not replace it. Each piece of content is carefully reviewed to ensure it reflects the genuine experiences and needs of our community. This approach helps us maintain the integrity of the information shared and ensures that our newsletter remains a trustworthy and valuable resource for everyone interested in the vibrant field of open education.

Your thoughts and feedback are invaluable to this process, helping us refine and improve our use of AI in creating a newsletter that truly resonates with and serves our community. Let’s continue to explore the potential of open education together, supported by the best tools available, used wisely and ethically.

Resources & Links

The Imagine If... thinking routine was developed by Project Zero, a research center at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Open: The Philosophy and Practices that are Revolutionizing Education and Science on JSTOR. (2024). Retrieved 20 April 2024, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv3t5qh3

Student Voices: Embracing Open Educational Resources at UTA | UTA Libraries. (2024). Retrieved 20 April 2024, from https://libraries.uta.edu/news-events/blog/student-voices-embracing-open-educational-resources-uta

Zara, M., Streeter, S., Allen, L., & Rowe-Morris, M. (2024). OER @ UTA [Google Slides]. UTA Libraries, The University of Texas at Arlington. https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1VdAy-1tkgnCEUtnyhelxpxrITJTU5K0t7j0BLccotYQ/edit?usp=sharing

Redefining Literacy for a Multimodal World

Foreword: Reflections and Evolutions (2023)

As a student at Texas Woman’s University, I found myself very interested in the cross section where literacy, technology, and the way we create and consume information come together. Multimodality and a Social Semiotic Theory of Literacy (original paper below) is a culmination of my research in 2021. My journey since then, particularly my role as an Open Educational Resources (OER) Librarian at the University of Texas at Arlington, has profoundly deepened and expanded my understanding of literacy, education, and technology. This foreword serves as my most recent reaction to and continued interest in the topic, reflecting the integration of my experiences and insights gained in the rapidly evolving landscape of open education and digital literacy.

Reflecting on 2021 Through the Lens of 2023

In my role as an OER librarian has further informed my perspective on these issues. Open educational resources have the potential to democratize education, providing access to a wealth of diverse, multimodal learning materials. This aligns with the need for a more inclusive and flexible approach to literacy, acknowledging the diverse backgrounds and learning styles of students. As an OER librarian, I advocate for and contribute to the creation and dissemination of resources that support this modern understanding of literacy, ensuring that educational materials are not only accessible but also relevant to today’s digital and multimodal world.

What’s Next (2023)

The challenge and opportunity lie in continuing to develop our understanding of multimodal literacy, keeping pace with technological advancements. My commitment is to contribute to this evolving field through research, writing, and preparing future educators to embrace a multimodal approach to literacy and learning.

Revisiting this paper has reinforced my belief in the need for a redefinition of communication and literacy that reflects our digitally interconnected world. Embracing this change is crucial for preparing our students to thrive in their future endeavors.

Multimodality and a Social Semiotic Theory of Literacy – Original Work (2021)

The landscape of learning and communication has changed dramatically over the past quarter-century. As the technologies (pencil and paper are considered a technology for communication) that we use to communicate evolve, the way we make and share meaning should change.

The Covid-19 Pandemic has opened the door for education reform. The 2020-2021 school year challenged educators to rethink how they teach. I am not sure that education and the “real” world have ever been more disconnected. Most would likely agree that we want our students to be prepared for their adult lives. We hope that when students leave our campuses, they have everything they need (skills, knowledge, experience) to function within and contribute to society. Why are we still preparing them for a world that looks like the 1950s? Or the 1980s? Or even the 2010s? We should be preparing them for the 2020s, the 2030s, and beyond.

In the photo, we see students before smart boards, smartphones, computers, etc., practicing financial literacy. It looks as if the students are role-playing a scene from a bank. Some students are bankers, and some are customers. The students are engaging in an authentic learning experience that reflects their time period. If a teacher recreated this lesson today, the picture would, and should, look different. There may be a computer on the desk, an ATM set up off to the side, and possibly a representation of mobile banking.

The problem we face now is that classrooms often use methods and pedagogy from the past and effectively prepare students for a time they will never see or need to navigate. There are plenty of reasons schools may not be using the most up to date methods in the classroom, such as curriculum, state, and district mandates, policies, politics, and textbook adoptions, a lack of high quality/updated professional development available to teachers, and even pre-service teacher programs that are outdated. The landscape of technology and communication has snowballed into an ever-changing, ever-growing, creator’s and information junkie’s paradise. According to Kress (2003), “it is no longer possible to think about literacy in isolation from a vast array of social, technological and economic factors.” We can count on change to continue to happen rapidly, forevermore.

“Our understanding of literacy has expanded beyond traditional written and oral language. The digital age has introduced a variety of modes – internet, devices, images, symbols, and more – creating a society rich in information. This evolution calls for a shift in classroom dynamics, transforming students from passive receivers of knowledge to active creators and critical thinkers.”

We no longer rely primarily on language (written and oral) to convey messages and connect with others. Language has long been the dominant mode of communication in the world of literacy. Literacy has traditionally been sequestered in the English, Language Arts, and Reading realm and is rarely thought of by the general public as the way we make and share meaning in all aspects of our lives. Information is no longer only found in books and on paper; we receive and create information using various modes: the internet, devices, images, signs, symbols, design, gestures, sounds, and language. Different modes of communication offer different understandings; “the world told is a different world to the world shown” (Kress, 2003). With the advancement of technology, all of these modes have been made more accessible and easier to produce, which has created a society overflowing with information. Students should no longer be in the position of knowledge receivers in the classroom, where teachers act as gatekeepers of information. Students should now be engaging in learning experiences that build them into knowledge finders, knowledge creators, critical consumers, and problem solvers.

We should be looking at literacy and communication from a different perspective, and we need to expand our understanding of literacy. Literacy can no longer be seen as language only and must bring into sight and practice using technologies that provide more access to make and share meaning in the various modes (Kress, 2003). Multimodal literacy and a semiotic theory of literacy provide a solid foundation, albeit reasonably new research, to build a better understanding of a multimodal approach to literacy and bring more relevant pedagogy into public education (Kress, 2003).

Multimodality (2021)

Humans communicate using a variety of modes to convey meaning. Everything we do, and everywhere we go, we interact with text of some kind. Text is no longer simply words on a page or spoken language. Text can be anything used to communicate. Street signs communicate laws and directional patterns. Facial expressions communicate our mood. Wearing a jacket communicates to others that you feel it is cold enough to cover up. A soft spot on a piece of fruit can communicate the ripeness or quality of the fruit. The way information is communicated matters because different modes of communication have different affordances. The affordances extended by a mode are “shaped by its materiality, by what it has been repeatedly used to mean and do (its ‘provenance’), and by the social norms and conventions that inform its use in context – and this may shift, as well as through timescales and spatial trajectories” (as cited in Kress & Van Leeuwen, 2004; Lemke, 2000; Massey, 2005).

The idea of multimodality stems from the New London Group’s (1999) theory of multiliteracies. This theory states that literacy varies in different contexts. To be literate is no longer one thing; that is, one can be literate in multiple ways and multiple Discourses. In the 1990s, the New London Group conceived of the term multiliteracies, highlighting a new perspective of literacy theory and practice. New technologies and an increasingly diverse population have spurred the need for understanding literacy differently or developing a “new literacy.” Additionally, the New London Group noted that helping students develop literacy through traditional reading and writing practices was not sufficient and called for students to engage in digital literacies (Wright, 2019). Linguistic diversity and multimodal forms of expression were the pillars on which the idea of multiliteracies was based (The New London Group, 1999).

Gee discusses in the New Literacy Studies (NLS) (2015) the shift happening as we become aware of the various modes that play into making meaning in our increasingly digital world. The NLS believed in “[following] the social, cultural, institutional, and historical organizations of people (whatever you call them) first and then see how literacy is taken up and used in these organizations, along with action, interaction, values, and tools and technologies” (Gee, 2015). The NLS members believe that it is not only the ‘private mind’ that experiences and builds meaning, but that everything we ‘read’ has been socially and culturally structured through shared lived experiences (Gee, 2015). Kress (2003) describes the theoretical change as one “from linguistics to semiotics-from a theory that accounted for the language alone to a theory that can account equally well for gesture, speech, image, writing, 3D objects, colour, music, and no doubt others”.

Brian Street, Literacy in Theory and Practice (1984) and Shirley Brice Heath, Ways with Words (1983) have helped researchers understand literacy more from a social and cultural viewpoint. Street’s (1984) ideological model helps us understand literacy in terms of concrete social practices and think about the ideologies in which different literacies are embedded. Literacy, of any type, only matters how it works with other social factors, including political, economic, social, and logical ideologies. Heath’s (1983) ethnographic study of how literacy is embedded in the cultural context of the three communities in the Piedmont Carolinas helps researchers understand that context and culture affect the way we use language outside of the home (Gee, 2015).

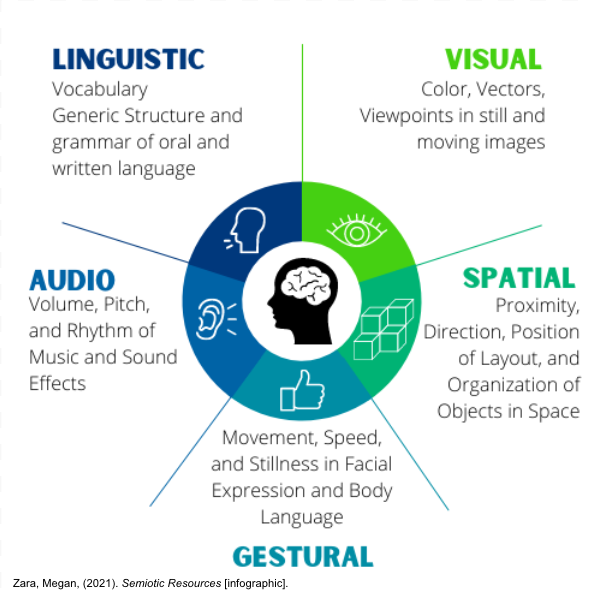

The prefix multi- alludes to the presence of monomodal texts; however, all texts are multimodal. Multimodal texts are print-based and digital texts that use more than one semiotic resource, or mode, to represent meaning potentials. Modes are socioculturally shaped resources for meaning-making (Kress, 2003; Serafini, 2015). Multimodality is the awareness of how the various modes work together to build meaning (Alvermann et al., 2013). There are five general modes of communication that are considered, in addition to the socio-cultural aspect of the text’s production. The linguistic mode includes what we traditionally understand literacy to be. It includes words and general structures of oral and written language. The visual mode covers colors, vectors, and angles/perspectives in both still and moving images. The spatial mode considers proximity, direction, layout, and organization of objects in place. The gestural mode includes movement, speed, stillness, facial expressions, and body language. Finally, the audio mode considers volume, pitch, rhythm, music, and sound effects. (Gee et al., 2012; Jewitt, Carey & Kress, Gunther, 2003; Shaumyan, 1987)

When analyzing traditional text, a book, there is more to the book’s meaning than just the words on the page. The reader should consider not only the words but the structure of the words on the pages. When we come to a page that only has text on half of the page, it communicates that we have reached the end of a chapter or section, and we can expect that turning the page will bring a new big idea. Is it a graphic novel? Are images included? Are the images dependent on the text? Is the text-dependent on the images? Who is the author, and what time period, culture, class level, gender, etc., did they produce this information? Is there an audio companion? Does the author narrate the book him/herself? A reader could continue to ask questions about the book and all of the meaning that can be gleaned from its words, structure, and position in society. Even an image with no words can be considered both visual and spatial, and depending on what is in the image, a gestural mode could be employed.

Language (linguistic mode) is no longer the only mode of communication that should be considered when analyzing the meaning of text. Language is now seen as one piece to the entire multimodal approach to literacy (Kress, 2010). Multimodal literacy requires a shift in thinking about meaning-making, away from simply what sounds and words mean within an alphabetic system, to a more socio-cultural understanding of how humans communicate (Gee, 2015; Kress, 2003, 2010) In order to embrace a multimodal approach to literacy fully, researchers should be studying meaning-making from a semiotic perspective. Social Semiotics provides the groundwork for building a more complete and relevant understanding of literacy (Kress & Van Leeuwen, 2004, Kress, 2010).

Semiotics (2021)

Semiotics is the study of signs, symbols, and icons and their use or interpretation (Kress, 2010; Serafini, 2015). In semiotics, “language constitutes the essence of language as an instrument of communication and an instrument of thought,” which allows readers to approach language from different perspectives (Shaumyan, 1987). In his book Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication, Kress (2010) explains that “the world of communication has changed and is changing still; and the reasons for that lie in the vast web of intertwined social, economic, cultural and technological changes.” Technology has changed the way people communicate, and the approach taken to build literate adults needs to change.

Studying multimodality and multimodal texts from a semiotic approach allows readers to access more potential meanings and interpretations. Social semiotics explores how humans derive meaning from the world around them. Charles Sanders Peirce (1991), one of the founders of semiotics, defines a sign as anything that represents (signifier) or indicates something else (signified). There are three categories of signs: icon, index, and symbol. An icon directly resembles or shares material qualities with its objects; for example, a picture of a cat represents a cat. An index holds an implied meaning; the signifier and signified share a logical relationship. For example, smoke indicates fire; a car horn may indicate traffic. Finally, a symbol is not inherently connected to the signified. There are no natural connections between the signifier and the signified. Symbols and their potential meanings are shaped by culture and social practices and interactions with the object in a specific context. For example, a solid line on a road indicates that cars may not pass. A solid line on a piece of paper could potentially separate information (Peirce, 1991). Symbols rely heavily on the use of other modes and cultural and social positioning to understand their meaning.

If we continue thinking of communication as solely language, we leave out part of the whole picture of communication. Words themselves are symbols and, therefore, share no logical connection to indicate meaning. The only way that meaning is understood by looking at written words or hearing oral language is to see them through a socio-cultural context. Words have meaning because we have been socialized to associate words (signifier) with things/ideas (signified) (Kress, 2010; Shaumyan, 1987; Peirce, 1991; Shaumyan, 1987).

Implications For the Classroom (2021)

At the time of writing this, I was a digital learning specialist. I worked directly with teachers to integrate technology in meaningful ways. There is a lot of talk and frustration around the idea that students are “digital natives.” The assumption that children come to school knowing how to use technology efficiently is dangerous because it means that educators are likely not focusing efforts on scaffolding the use of technology and digital literacy principles critical in preparing students for the future. Educators must scaffold both new technical skills and multimodal literacies (Mills, 2010). Not all students have access to technology before entering school and, therefore, do not have the prior knowledge to use technology without support effectively. Discussions about multimodal literacy practices of children have overlooked the fact that many of the students who are not coming to schools with experience using technology are not from the dominant culture (Mills, 2010).

Although teachers cannot expect students to come to the classroom knowing how to read multimodal texts or use technology for learning, teachers need to remember that students are immersed in a very connected and digital society. Their discourse includes text language, high-speed internet, information at their fingertips, video games that read to them and connect them to others outside of their inner-circle, cars that direct their parents where to go, and many have had their own device from a very young age. They see and understand their world through all of the modes and expect a multimodal approach to learning. Embracing and scaffolding for the use of technology and multimodal analysis honor the society and culture in which young people currently live. Ideally, the classroom and learning experiences should emulate the world in which students will eventually enter as adults. If they are not taught how to make meaning, create, and engage with multimodal texts, we are doing them a disservice (Mills, 2010).

Language needs a more relevant definition. Text is no longer simply the words on a page. Communication has changed dramatically, bringing connectedness to the forefront of all interactions. Our students are disconnected from what it means to live and function in a digitally-run world. Understanding literacy through multiple modes of communication and analyzing all texts through a semiotic lens will positively impact student learning and their transition into adulthood.

Research in multimodal literacy and a social-semiotic theory of literacy is still new and uncharted. The nature of technology and how quickly it evolves, and changes will dictate the fluidity and flexibility that a solid new theory and pedagogy should have. Moving forward, I hope to contribute to this body of knowledge. I plan to pursue research opportunities and to read and write widely on the topic. I am interested in what multimodal discourse analysis can tell us about learning and social interaction. Ultimately, I would love to help prepare pre-service teachers to teach and continue learning around multimodal literacy.

References

Gee, J. P. (2015). The New Literacy Studies. The Routledge Handbook of Literacy Studies Routledge. 10.4324/9781315717647.ch2

Jewitt, Carey & Kress, Gunther. (2003). Multimodal Literacy. Peter Lang.

Kress, G. (2003). Literacy in the New Digital Age. Routledge.

Kress, G. (2010). Multimodality: A social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. Routledge.

Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2004). Multimodal discourse: The modes and media of contemporary communication.33(1), 115-118.

Mills, K. A. (2010). Shrek Meets Vygotsky: Rethinking Adolescents’ Multimodal Literacy Practices in Schools. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 54(1), 35-45. 10.1598/JAAL.54.1.4

Serafini, F. (2015). Multimodal Literacy: From Theories to Practices. Language Arts, 92(6), 412-423.

Shaumyan, S. (1987). A Semiotic Theory of Language. Indiana University Press.

Wright, W. E. (2019). English language learners: Research, theory, policy, and practice (3rd. ed.) Calson.

Zara, Megan. (2021). Does it have to be text? [infographic].

Zara, Megan. (2021). Semiotic Resources [infographic].

The One Where I Balance AI, Ethics, And Mental Health in Academia

I want to share something deeply personal and professionally significant – my journey with AI (Artificial Intelligence), specifically ChatGPT, in academia. It’s not just about the technology; it’s about how I navigate it with integrity, innovation, and a mindful approach to my mental health.

Understanding ChatGPT: The AI Assistant in Academia

ChatGPT is an advanced artificial intelligence program created by OpenAI. GPT stands for Generative Pre-trained Transformer. It functions by processing and generating text in a way that closely mimics human language. This ability allows it to engage in interactive conversations, respond to a wide range of questions, and even assist with tasks like writing, summarizing information, or offering explanations. It learns from an extensive database of language examples, enabling it to understand context, interpret requests, and provide relevant, coherent responses. Basically, ChatGPT acts as a virtual assistant that can converse and assist with various text-based tasks.

Navigating Ethical Waters: AI, Copyright Law, and Creator Rights

There are ongoing concerns and discussions regarding GPT and copyright law, particularly in relation to the rights of creators. These concerns stem from how GPT, like other AI language models, is trained on extensive datasets that include copyrighted materials. This raises questions about whether the use of such data for training constitutes fair use or infringement. Additionally, there’s debate over the rights to the content generated by GPT: who owns it, how it can be used, and whether it infringes on the original creators’ rights. These issues highlight the need for clearer guidelines and regulations in the evolving intersection of AI technology and copyright law. There are strong points being made on both sides.

As an educator, librarian, and researcher, I’ve integrated ChatGPT into my work. But let me be clear: this is done with a strong commitment to ethical practices and academic integrity. I use ChatGPT as a research assistant, a thought partner, and sometimes, a writing aide. It’s a supplementary tool that sparks creativity, aids in data analysis, and helps draft initial ideas. But, and this is crucial, I always critically evaluate and verify the AI-generated content to ensure accuracy and authenticity.

Balancing AI and Originality: Transparency in AI-Assisted Work

I use GPT as a supplementary tool for ideation, data analysis, and drafting preliminary content. However, I maintain a critical approach, thoroughly reviewing and verifying all AI-generated information. I am transparent about the involvement of AI in my work, clearly distinguishing between AI-assisted content and my original contributions. For instance, ChatGPT assisted in gathering and organizing my thoughts and ideas on integrating AI into my work. I find it incredibly productive to “brain dump” into a ChatGPT conversation and allow it to reorganize and help me bring clarity to my ideas.

I am aware of the potential for bias in AI-generated content and take proactive steps to mitigate this, ensuring my work represents a fair and balanced perspective. I respect intellectual property rights and adhere to established guidelines on authorship and attribution in academia. That said, I am also open to and curious about the uncharted landscape of creator rights and OpenAI. On November 7th, 2023, Creative Commons released a response to the United States Copyright Office’s Notice of Inquiry, seeking public feedback about the intersection of copyright law and artificial intelligence. Creative Commons has developed nuanced positions on the intersection of AI and copyright law. A key belief is that the use of copyrighted materials for AI training is generally seen as fair use, a perspective that recognizes the importance of accessing a broad range of data for AI development.

Creative Commons also advocate for copyright protection of AI-generated outputs, particularly when these outputs involve significant human creative input, emphasizing the value and originality contributed by human involvement. In cases of potential infringement by AI, Creative Commons supports the application of the substantial similarity standard, which assesses the degree of likeness to existing copyrighted works. Additionally, they emphasize the importance of allowing creators to explicitly state their preferences on how their works are used in AI applications. However, they acknowledge the limitations of copyright law in fully addressing the complexities surrounding generative AI, suggesting that while copyright is a crucial part, it’s not a universal remedy for all the ethical and legal intricacies AI presents (Angell, 2023).

In using GPT, my goal is not to replace human intellect and creativity but to augment it. This technology serves as a catalyst for innovation, enabling me to explore innovative ideas and perspectives while still being grounded in ethical research practices.

AI as a Mental Health Ally: ChatGPT in My Daily Life

In addition to the academic and ethical considerations, I also embrace ChatGPT as a tool that significantly supports my mental health needs. As someone managing bipolar disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and attention deficit disorder, I find ChatGPT to be more than just a research assistant; it’s a supportive ally in navigating the daily challenges these conditions can present.

ChatGPT’s prompt responses and ability to organize and structure information help me manage the symptoms, especially during periods of decreased focus. The AI’s capability to assist with drafting and brainstorming alleviates the pressure and anxiety that often accompany the initial stages of the creative process, fostering a more relaxed and conducive environment for my work.

Moreover, during shifts in my energy levels and mood, ChatGPT serves as a steady and consistent resource. It helps support the momentum of my research and writing projects, ensuring continuity even during fluctuating personal circumstances.

The adaptability of ChatGPT is particularly beneficial. It aligns with my varying cognitive needs, providing assistance that is responsive to my mental state at any given moment. Whether I require detailed analysis or just a starting point for my thoughts, ChatGPT’s flexibility is a key factor in making my academic endeavors more manageable and less stressful.

A Balanced Approach: Merging AI with Mental Health Advocacy in Academia

In essence, ChatGPT is not only a tool for academic advancement but also a significant part of my strategy for managing mental health in a professional context. It contributes positively to my mental well-being, enabling me to achieve a balance between my professional aspirations and personal health requirements. This harmonious integration of technology into my work life underscores my commitment to not just academic excellence but also to self-care and mental health advocacy.

It’s about finding a balance. ChatGPT aligns with my cognitive needs, adapting to my mental state, making my academic endeavors more manageable. This AI isn’t just a tool for my work; it’s a part of my strategy to manage mental health in a demanding professional environment. It allows me to pursue academic excellence while also prioritizing self-care and mental health advocacy.

In embracing AI, I’m not just advocating for technological advancement. I’m also pushing for an approach where mental health is given the space and attention it deserves, especially in high-pressure environments like academia.

Epilogue: Evolving with AI

As I navigate this evolving journey, I consider myself a learner as much as a librarian and researcher. In exploring the responsible and ethical integration of AI in academia, I’m also constantly learning about balancing my professional endeavors with my well-being. It’s my sincere hope that sharing my experiences will encourage others to discover their own equilibrium between technology, career aspirations, and personal health.

Thank you for reading, and here’s to a future where technology not only advances our work but also supports our holistic well-being!

Angell, N. (2023, November 7). CC Responds to the United States Copyright Office Notice of Inquiry on Copyright and Artificial Intelligence. Creative Commons. https://creativecommons.org/2023/11/07/cc-responds-to-the-united-states-copyright-office-notice-of-inquiry-on-copyright-and-artificial-intelligence/

The Open Road to Equity: Navigating Open Educational Practices

This post is a reflective response to “Framing Open Educational Practices from a Social Justice Perspective” by Bali, M., Cronin, C., & Jhangiani, R. S. (2020). It explores the multifaceted nature of Open Educational Practices (OEP), emphasizing the need for diverse, equity-focused strategies in education. The article highlights the role of OEP in bridging pedagogical, social justice, and learner-centric approaches, and calls for a nuanced application of OEP that prioritizes the needs of those furthest from justice.

Redefining Openness in Education: Beyond Content Sharing

Open education transcends mere content sharing, embodying an attitude of vulnerability and open narration of our evolving practices. As Bali et al. (2020) articulate, “Openness can also be conceived of as an attitude or worldview” (p. 1), emphasizing the human element in education. The contrast between Open Educational Practices (OEP) and Open Educational Resources (OER) is pivotal, with OEP focusing on the process over content, student-centered over teacher-centered, and evaluating the potential social justice impact. This is echoed in the definition of open pedagogy as “an access-oriented commitment to learner-driven education” (Bali et al., 2020, p. 1).

Embracing Vulnerability: A New Perspective on Educational Practices

In the context of Open Educational Practices (OEP), I often confront the ease of defaulting to traditional, teacher-centered methods. These methods, while familiar, limit the dynamic potential of learning by keeping control in the hands of the educator. In contrast, my philosophy as an educator aligns more with being a facilitator or ‘lead learner,’ advocating for student-driven learning. OEPs offer a variety of frameworks that empower students to take charge of their educational journey, challenging the traditional norms and encouraging more personalized and impactful learning experiences. This shift is crucial for fostering a more engaged and equitable learning environment.

Balancing Pedagogy, Social Justice, and Learner Engagement in OEP

OEP’s transformative potential indeed spans multiple dimensions, bridging the gap between pedagogical, social justice, and learner-centric approaches. To delve deeper, we must understand the three axes of OEP as identified by Bali et al. (2020). First, the shift from content to process, emphasizing dynamic interactions and knowledge construction. Second, the move from teacher-centered to student-centered learning, empowering students as drivers of their educational journey. finally, the evolution from purely pedagogical objectives to incorporating social justice, addressing economic, cultural, and political inequalities. This framework not only aligns with the role of an educator as a ‘lead learner’ but also highlights the need for a critical examination of OEP’s impacts, which can range from transformative to potentially negative. This critical lens is essential to ensure that OEP’s potential is harnessed for equitable and inclusive educational outcomes.

However, as highlighted by Bali et al. (2020), the influence of OEP extends beyond positive outcomes, sometimes producing varied or even adverse effects (p. 3). This complexity necessitates a thorough and critical examination of how OEP aligns with and impacts social justice objectives. Understanding this spectrum of influence is key to responsibly implementing OEP in a way that truly advances equitable and meaningful education.

Shaping Our Educational Narrative: A Call to Action

At the University of Texas at Arlington, while we embrace the economic aspects of Open Educational Practices (OEP) through initiatives like the UTA CARES grant, our journey towards a truly open educational environment is ongoing. Understanding OEP through the lens of diverse strategies across three axes, as Bali et al. (2020) suggest, is essential. We must strive for a comprehensive, individualized approach that prioritizes equity, especially for those furthest from justice.

This leads us to a pivotal question for fellow researchers: How can we expand our understanding and application of OEP to ensure that all voices are not only heard but also actively shape the educational narrative?

References:

Bali, M., Cronin, C., & Jhangiani, R. S. (2020). Framing Open Educational Practices from a Social Justice Perspective. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2020(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.5334/jime.565

Okuno, E. 16 November 2018. Equity doesn’t mean all. FakeQuity [online]. Available from: https://fakequity. com/2018/11/16/equity-doesnt-mean-all/.