Human-centered learning. Open leadership. Creative work.

I build human-centered learning ecosystems, documentation, and creative learning tools that help people turn meaningful work into something clear, doable, accessible, and repeatable.

Color Your Calm is not just a coloring book. It’s a research-informed reset rooted in care ethics, created for caregivers, educators, helping professionals, and anyone doing emotional labor.

Inside are 25 stress-relief coloring pages plus inquiry prompts, affirmations, and short reflections on the real inner landscape of care work: burnout, boundaries, guilt, nervous system regulation, and support. This book is designed to be used in real life, in small moments, without perfection.

It also includes Reverse Coloring, a simple creative practice that turns marker bleed-through and “mistakes” into new designs, with repeating prompts you can reuse anytime.

Use it for a two-minute reset, a longer unwind, or a gentle check-in. The goal is not productivity. The goal is care.

Price includes Free Shipping within the US.

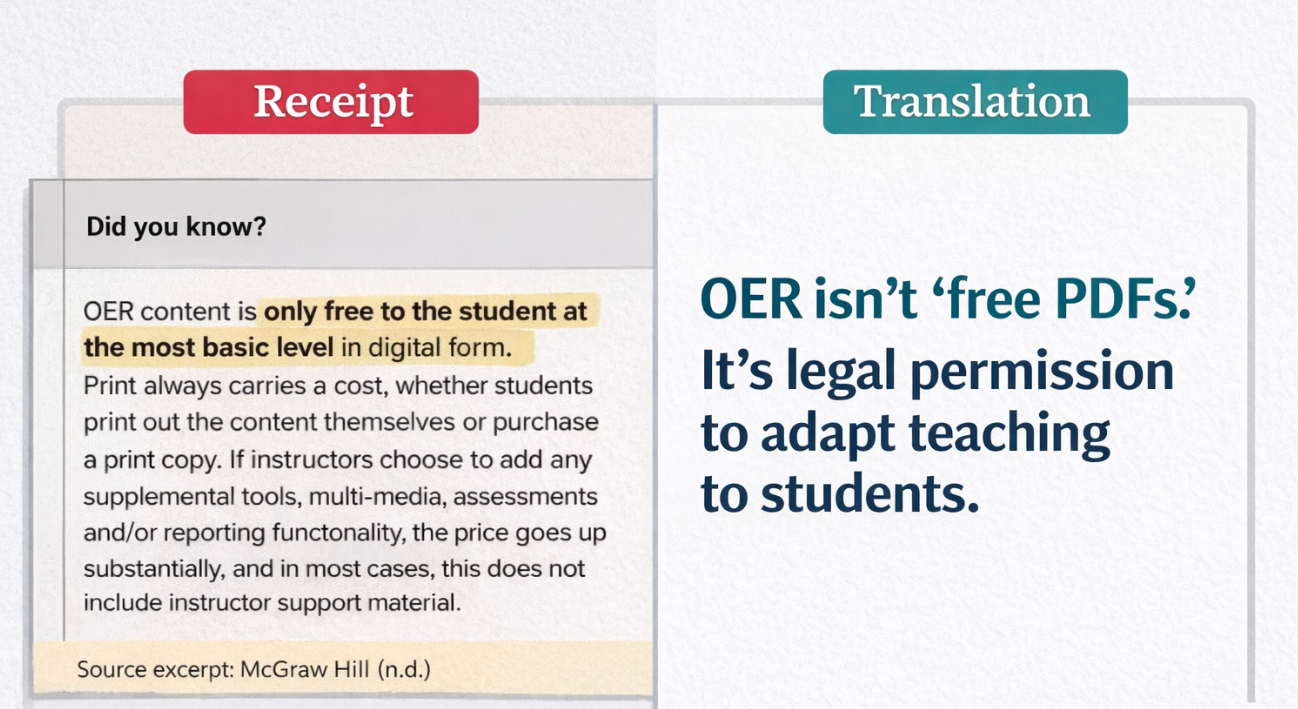

At the UT System Momentum on OER Convening, I kept thinking about what higher education too often skips: the moment before adoption. The part where educators need structure, not cheerleading; method, not mandate. In this post, I reflect on that experience and share openly available resources, including a mini-lesson series and the OER Tracker, designed to make OER exploration more rigorous, transparent, and usable across roles.